Knowledge Base

New leitmotiv

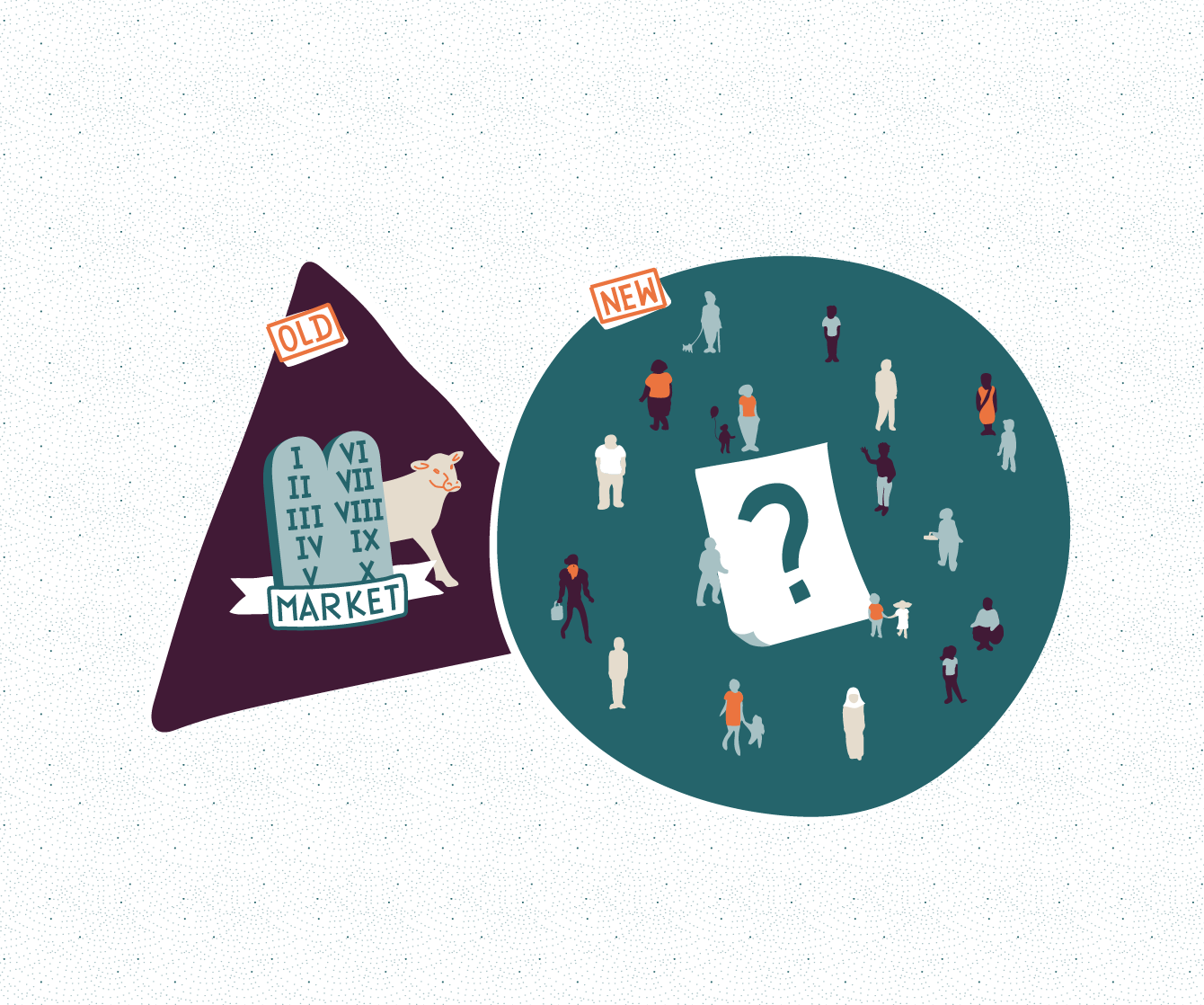

After decades of overly naive market belief, we urgently need new answers to the great challenges of our time. More so, we need a whole new paradigm to guide us.

The crisis of a former paradigm

A paradigm not only consists of a set of technical instruments to solve the main challenges. It also needs some overall guidelines. This is one of the Forum’s main working hypothesis.

As a sign of a missing paradigm that holds societies together, liberal democracies today are facing their most serious crisis since World War II. Over three decades, economic policies have been dominated by the belief of reduced state influence and market-driven globalisation. While this brought a lot of benefits, it has created fundamental socio-economic problems that have grown ever-more apparent since the Great financial crisis in 2008. These include dangerously rising levels of inequality, recurrent financial crises fueled by a high degree of instability in financial markets, the underfunding of public infrastructure, environmental crises as well as a loss of credibility of the narrative that globalization will benefit all. The failure of the decades-old paradigm of market-based globalization and economic policy has provoked an overall sense of loss of control on an individual and political level.

History shows that when existing paradigms fail as guiding principles for politics, a vacuum is created that populist forces in particular are quick to exploit with simple but dangerous answers, as reflected in the rise of populism in Western democracies in the last decade. What is urgently required is a new paradigm, a new leitmotif – to replace the deceptively simple doctrine of the infallibility of markets with something better suited to solve the major problems of our time. This exceeds just technical answers in including a guideline for an economic policy – one that creates sustainable prosperity in a financially stable environment for as many people as possible. Otherwise, it will be difficult to solve today’s most urgent challenges – whether climate change, inequality or the crisis of globalization. And otherwise, it will be hard to convince people that there are better answers than the ones offered to them by populist forces.

What went wrong

An ever-growing mountain of empirical evidence indicates that large parts of today’s crises are to be linked to the late effects and collapse of the market-liberal paradigm that has guided policymaking in most of the world since the 1970s.

From the idea of efficient and self-stabilizing financial markets to the belief that an ever-larger financial sector increases society’s well-being, and market-based emissions trading can serve as a panacea to the climate crisis, reality – and new research – has shown the true costs of decades of adhering to the market-based paradigm. The global financial crisis revealed the inherent tendency of financial markets to boom-and-bust-cycles, and the most recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2021) suggests that the current trajectory of the global economy with its high level of carbon emissions is incompatible with the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement, also indicating that market-based emissions trading is not sufficient or even creates instability itself.

Other pillars of the old paradigm, such as the idea that reduced state influence is a prerequisite for economic dynamism, the dogma of expansionary fiscal austerity and the trickle-down hypothesis, according to which tax cuts for the rich will “trickle down” and effectively increase prosperity for all, are also crumbling. Growth has not trickled down, instead Income and wealth inequality today is much higher than in the 1980s creating serious societal problems. In the European Union as much as elsewhere, the unconditional regulatory fixation on reducing annually fixed deficit ratios led fiscal policy to be systematically too procyclical, exacerbating cyclical swings and crises, while the dogma of reducing state interventions has led to serious investment gaps in infrastructure In Europe as well as in the US.

Nowhere has the predominance of the market-based paradigm been taken more to its extremes than with the idea that free trade generally increases overall economic welfare and benefits from globalization would outweigh any of the costs.

How compensation would be provided by the winners to the losers was only an afterthought for most economists. In reality, compensation was barely forthcoming, and technology and globalization have created socio-economic disruptions and left entire regions behind. The vacuum created by the loss of individual and political control was quickly filled by populists.

All in all, it appears that market-liberal thought-leaders have largely over-estimated the capacity of markets to regulate in case of major challenges, e.g. when it comes to very long-term challenges as the fight against climate change. In other cases, liberal markets have created enormous challenges as in financial markets. This leads to the overarching question on how to re-balance the roles of markets and common societal action.

New Economy in Progress

Since the critical financial crisis in 2008, the search for a new paradigm much more adequate than the former market-preference to rise to today’s challenges has accelerated. And, while a coherent new paradigm is not yet ready, a lot of new answers and actors have emerged.

Emerging new answers include concepts that turn around how to make financial markets more stable – and serve the real economy, as well as ideas on how to avoid austerity policies, or on how to design good instead of bad jobs.

Research on central elements of a new paradigm turns around the question of how to redefine the role of the state versus markets. It’s also about redefining which other goals to follow if not GDP, as the typical goal during the market-liberal order has major downsides when it comes to measuring and ensuring economic, ecological, or societal sustainability. This also means redefining Europe and the euro architecture, defining long-term fiscal policy beyond the dogma of austerity, and redesigning the global trading system for the benefit of all. Whatever new guiding principles will take over, they should help to reduce inequality, make finance work for the real world again, better handle socio-economic disruptions due to globalization and technological change, and save the climate without counting solely on market forces that have contributed to many of the problems, or have shown to be inadequate to solve them.

In our understanding, a new paradigm needs to be more than the sum of a number of technical solutions.

A new paradigm very generally requires a focus on the long term in decision-making; better systematic inclusion of the consequences that potentially disruptive developments such as globalization, digitalization or climate change entail socially; better anticipation of possible market failures in policymaking; and a better understanding of risks.

Societies need guiding principles that help policymakers find adequate answers to the main challenges and re-elicit people’s trust in that policymakers follow goals and approaches based on a large societal and scientific consensus. The question is which new guidelines will help to solve today’s challenges bearing in mind that the answer will not be to shift from market-fundamentalism to a paradigm where all challenges are to be solved by the government.

A decisive societal shift is usually triggered by a major crisis that heavily discredits the old understanding – as the stagflation helping the market-liberal shift in the 1970s. The search for new answers then gains momentum with more and more supporters of the old order opening up to new ideas, whether in research, media or policy advocacy. However, as history shows, a new paradigm can only replace the old when there is a convincing new set of guiding principles. This set then starts to dominate research, public debates, and policymaking.

Developing such a new paradigm requires a behavioral change in policy making, new criteria and tools and a different lingo and logic in academic and public discourse. The challenge is to replace the simple narratives of the former all-too-market-dominated paradigm. Such a shift requires time, is driven by a deepening crisis of credibility of the old paradigm, and crucially depends on a progressive shift of mainstream-thinking towards an increasingly convincing new set of guiding ideas for policy making.