GLOBALIZATION

What were the Driving Forces in the 2019 UK General Election?

Thiemo Fetzer with an analysis.

BY

THIEMO FETZERPUBLISHED

13. DECEMBER 2019READING TIME

7 MINThe 2019 UK General Election has provided Boris Johnson with a significant parliamentary majority – yet, at the same time, it will have disappointed the majority of voters. Only 47% of voters supported pro-Brexit parties, while 53% of the votes being cast for anti-Brexit or pro-2nd Referendum parties – nevertheless, the first-past-the-post electoral system grants 57% of the seats to the Conservatives. The announcement of the resignation of Jeremy Corbyn’s is setting the stage for a leadership contest, in which an analysis of what went wrong, is a central element. So, what are some of the features that make the 2019 general election stand out and could feature in an explanation behind what was driving the election result?

Turnout was lower in 2019 relative to 2010

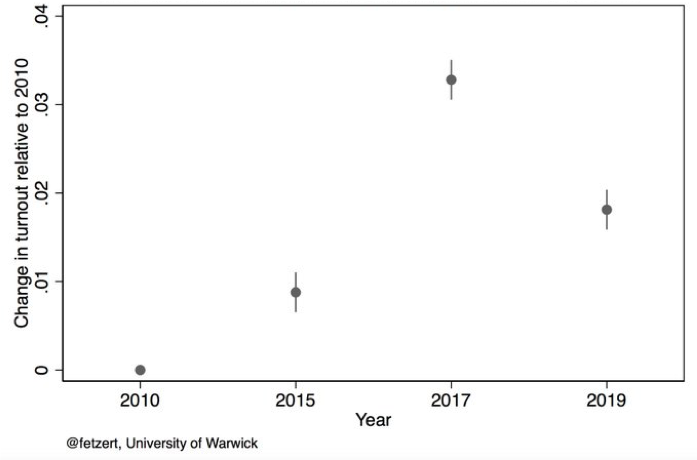

The first main observation is that turnout in the 2019 General election was significantly below the 2017 general election: across constituencies, on average, turnout was 1.7 percentage points lower. Many voters perceived to have only the choice between two perceived evils, as both Boris Johnson as well as Jeremy Corbyn were hugely unpopular. Yet, Boris Johnson had a clear advantage by being less unpopular. Given that choice, many of the crucial swing voters may have simply decided to stay home. The surprise recovery that Labour staged in 2017, starting out with similarly poor opinion polling as in 2019, was not repeated. Despite significant increases in electoral registrations, many people were added to the electoral rolls in districts or constituencies, that would not turn out to be marginal in the 2019 contest.

The 2017 GE campaign was remarkable as it saw, on average a turnout that was more than 3 percentage points higher, compared to the 2010 General Election. Part of this mobilization effect may have been down to a very effective campaign run by Labour, while the Conservatives campaign was full of blunders. The 2017 increase in voter mobilization was partly down to an increase in young voters turning out and being mobilized, partly by a very sophisticated online campaign by Labour. In 2019, it appears that the Conservatives have learned from their lesson in 2017, spending significant resources on online advertisements.

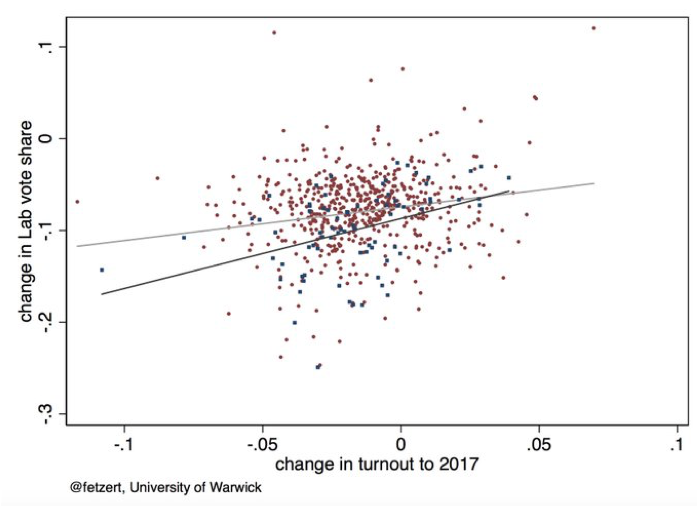

Lower turnout hurt Labour

The lower turnout seems to have had an impact on the electoral support for Labour. While Labour lost significantly across the whole of the country, the reduction in Labour support measured as share of the vote appears particularly pronounced in constituencies that saw a more pronounced drop in turnout – see Figure 2. The gradient is even steeper among the constituencies that the Conservatives gained from Labour. This suggests that Labour has not been able to mobilize their traditional voter base, with many of those turning out in 2017 deciding to stay at home in 2019. Given that the stakes in the 2019 election were so high, this suggests that Labour in 2019 was inherently less attractive to voters compared to Labour in 2017, with many deciding to stay at home. Naturally, this raises the question to what extent this was due to the policy platform that Labour had to offer or whether it was down to the perceived qualities of the party leadership. One may be tempted to say it was the former: after all, 2017 saw the same Labour shadow prime minister Jeremy Corbyn running. This may give rise to the notion that possibly, Labour’s stance on Brexit is what hurt the party. Yet, this appears not to be the case.

Vote splitting among progressive parties gave the Conservatives an advantage

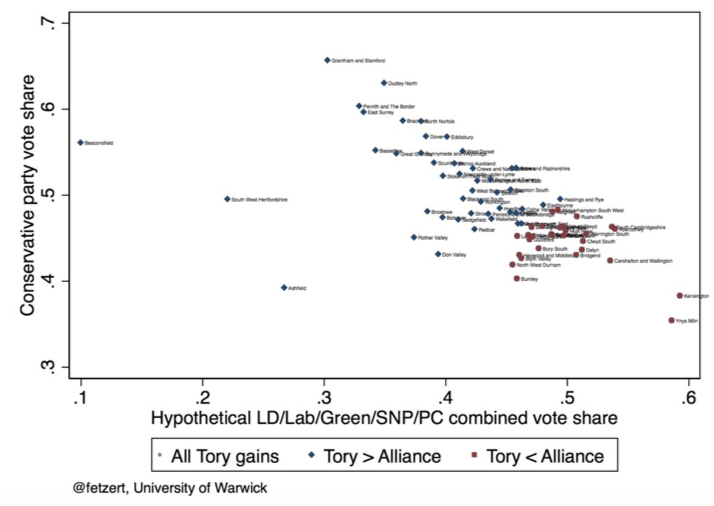

Another important factor that drove the election results was the fragmented progressive opposition. In some constituencies, voters had the choice between three or even four progressive candidates, while the Conservatives and the Brexit Party implicitly had sealed an electoral pact.

The Conservative Party was well aware of the division in the opposition. Much of this division was down to the perception among voters that Jeremy Corbyn would be a poor consensus candidate for the office of Prime Minister. The fragmentation of the progressives allowed the Tories to achieve a net gain of 66 seats. If the opposition parties had united under a “remain alliance” candidate in every constituency, there would have been up 30 fewer seat losses and a hung parliament would have been more likely (see figure 3).

To what extent did Brexit matter?

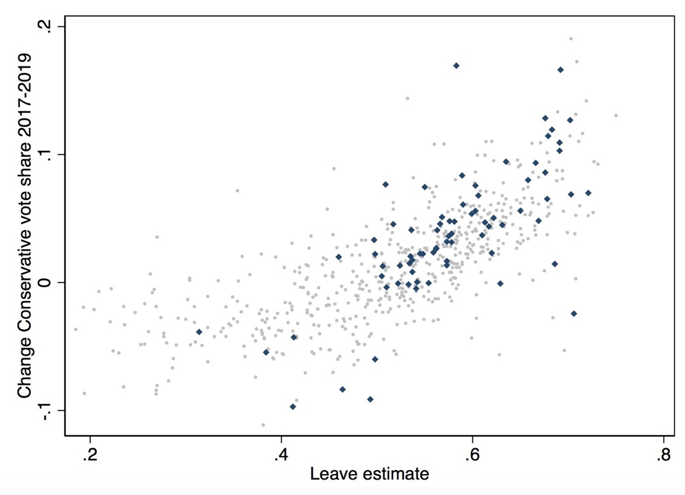

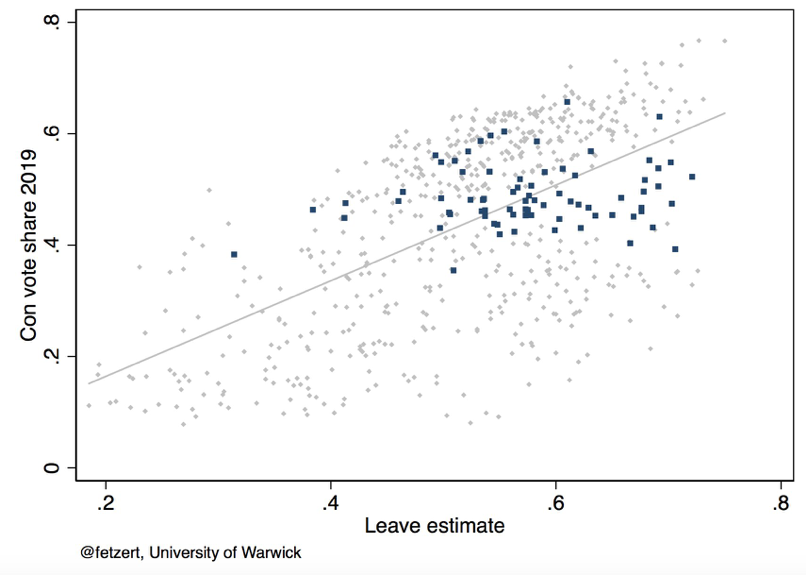

There is a temptation to see the 2019 General election only through the prism of Brexit. This is particularly tempting for some parts within Labour, which has failed to define a coherent Brexit policy since 2016. To what extent did Brexit matter? For the Conservatives, it is noteworthy that, on average, they saw an improvement of their vote share in constituencies that were more prone to support Leave (see Figure 4).

Yet, a regression analysis nevertheless highlights that the Leave vote share only explains a relatively small part of the variation in the Conservative vote share both in 2017 and 2019. This suggests that empirically, the support for the Conservative party in 2019 was not all down to Brexit, and opposition parties could have performed much better, independent from Brexit.

For Labour, the question to what extent Brexit was a feature of its poor performance is particularly relevant, given that the party failed to come up with a coherent, consistent and unambiguous Brexit policy. The losses in the Labour party’s vote share, however, can’t really be well explained by the different levels of support for Leave in the 2016 EU referendum.

The Labour Party lost votes in almost all constituencies – on average, around 8 percentage points, both in the constituencies that strongly supported remain, as well as in the bulk of constituencies, where the Leave vote was between 40-60%. Only in the constituencies in which support for Leave was above 65% there appears to be a pattern, whereby Labour’s losses were more pronounced. This suggests that Labour’s poor election performance transcends the issue of Brexit.

This is confirmed by recent opinion polling. Only a minority of voters that switched from Labour in 2017 to other parties cite the party’s stance on Brexit. The dominating issue was the perceived poor leadership. This suggests that the poor performance of Labour in 2019 is partly of its own making by electing a leader, that for the vast amounts of voters was deemed unelectable.

Unsettled times ahead

The 2019 General Election has, once again, highlighted, that the UK’s electoral system produces outcomes that essentially, are deeply unrepresentative. The Conservative party manifesto, rather than breaking this chasm, is bent on exacerbating the issues of poor representation. The 2019 General election was the fourth one that was held with unchanged electoral boundaries since 2010. This implies that constituency boundaries may be redrawn soon in a fashion that may provide even more advantage to the Conservatives in upcoming elections. The fact that the SNP is the only opposition party that won as a result of the election. By winning almost all Scottish seats, it will be close to impossible for any single opposition party to win a majority within the UK’s present electoral system.

The conclusion from this is self-evident: the opposition only has a chance to win any future election, if it forms a broad and centrist but progressive platform together with other opposition parties. The responsibility here clearly lies with the Labour Party, which was unwilling to be part of a broad electoral pact. The present leadership contest within Labour and the Liberal Democrats should fully focus on electing party leaders that can enable such a platform, which will have to move beyond classical party organizations and hierarchies, to emerge.

If they fail in this, a Conservative government will rule England and Wales in the foreseeable future.